Water jugs and BFS

Using graphs to solve puzzles

Random highschool memory: while waiting for some class, I was pondering a puzzle. You know, one of these wolf, goat and cabbage puzzles, only a bit knottier. I was just starting to take programming classes at school, and as I was searching for the solution, another puzzle, much trickier, occurred to me: write a program to solve the puzzle. Between writing “2D games” with ika and doing seemingly pointless exercises at school, I felt I had no handle whatsoever to approach this problem. After thinking about it hard for some time I gave up.

A few years later I encountered another famous puzzle - the water pouring puzzle. Though I’ve solved variations of it before, for some reason this time I remembered my meta-puzzle from highschool, and this time, having covered CS fundamentals, after some thought the solution clicked. It was all graphs!

The water pouring puzzle graph

Here’s the simplest version of the puzzle I know: you have two empty jugs of water, of volumes 3 liters and 5 liters. You’re next to an infinite source of water so you can fill up the jugs as much as you want, you can pour them into each other, and you can empty them completely. Your task is to have exactly one jug full of 4 liters of water, and there’s no way to make any measurements other than “completely full” or “completely empty”.

Here’s the solution (spoiler alert), referring to the 5-liter jug as J5 and the 3-liter jug as J3:

- Fill up

J5. - Pour

J5intoJ3untilJ3is full, leaving 2 liters inJ5. - Empty

J3. - Pour the remaining 2 liters from

J5toJ3, leaving 2 liters inJ3. - Fill up

J5. - Pour

J5intoJ3untilJ3is full, leaving exactly 4 liters inJ5. Done!

Now the real task is to write a program that, given the volumes of the jugs and a target volume, will either print instructions to get to the target volume or let us know that the mission is impossible.

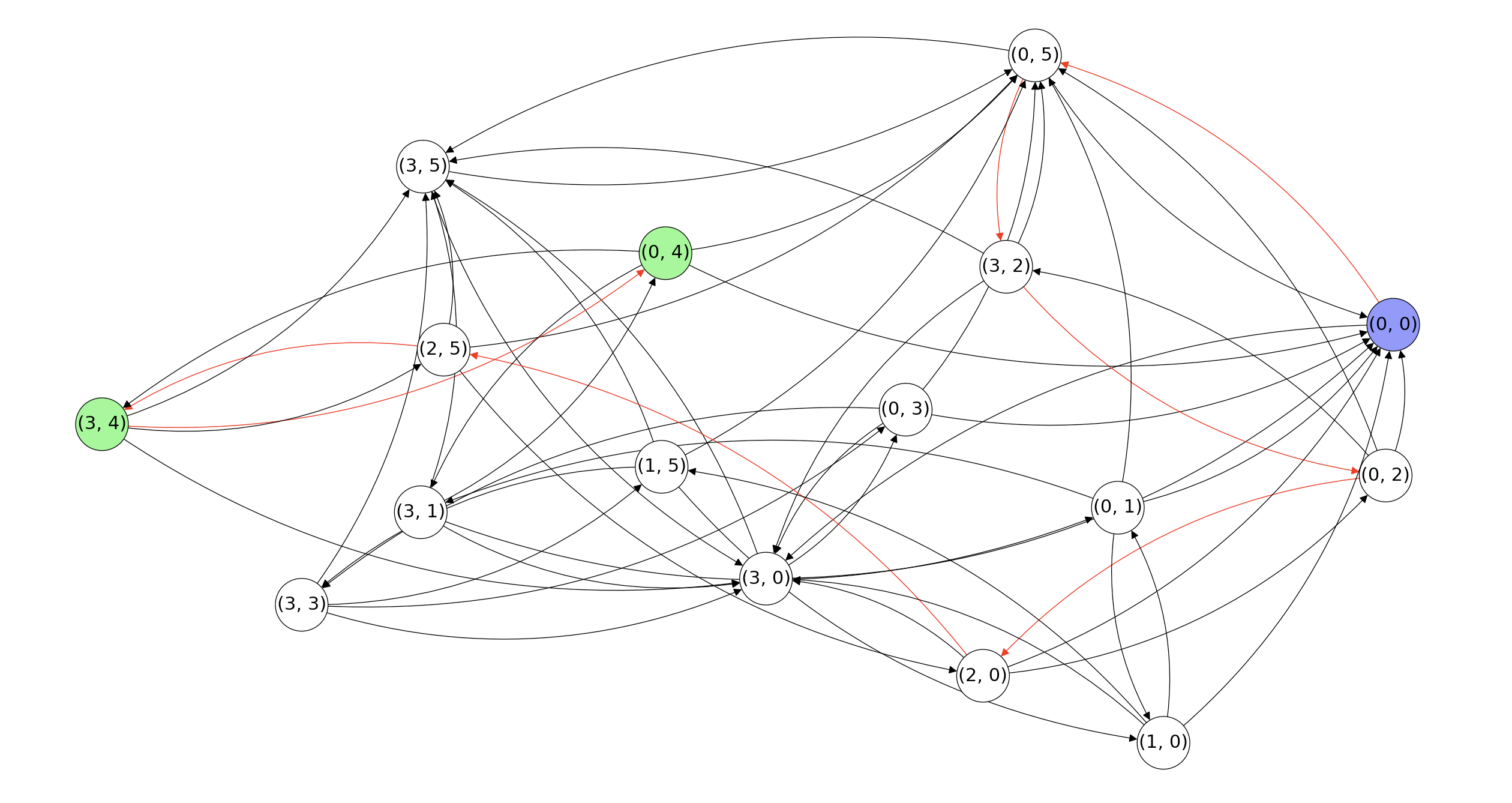

The way we’ll approach this is by treating each state of the pair of jugs as a node in the graph of all possible states. My notation for states will be (amount of water in J3, amount of water in J5). We’ll create an edge

from node (a, b) to node (c, d) if there’s some legitimate, atomic action we can take in state (a, b) to arrive at state (c, d). For example, we’ll draw an edge from (0, 5) to (3, 2) because in the former state we can pour J5 into J3 until J3 is full, arriving at the latter state.

The key insight is that in such a graph, a path from the node corresponding to the initial state to the node corresponding to the desired state is equivalent to a solution - we can use each edge to reconstruct the required action. And we can use BFS to search for such a path, and, if it exists, get the shortest possible solution! Quite neat. Formulating the problem like this is an instance of a state space search.

Here’s how the full graph for the (3, 5) pouring puzzle looks like, with the starting node, target nodes and path highlighted:

Of course we can implement BFS on this graph without creating the graph in memory. Let’s walk through a simple implementation in Python.

First let’s get the jug volumes:

a = int(input('Enter jug A volume: '))

b = int(input('Enter jug B volume: '))

t = int(input('Enter target volume: '))

a, b = min(a, b), max(a, b) # a will contain the smaller jugDefine a function to identify a node corresponding to the target state:

def is_solved(state):

return t in stateNow a less trivial function - finding all neighbors of a state. At this point we’re not concerned with whether or not we’ve already seen some neighbor, we’ll just generate all of them and take care of bookkeeping later. Also, some nodes might be neighbors of themselves (e.g. if jug A is already empty we can still “empty” it), but again that will be taken care of in the same BFS bookkeeping.

While we’re at it we’ll also annotate each edge with the description of the action so we can later print it.

def get_neighbors(state):

a_to_b = min(state[0], b - state[1])

b_to_a = min(state[1], a - state[0])

return [

((a, state[1]), f'Fill J{a}'),

((state[0], b), f'Fill J{b}'),

((0, state[1]), f'Empty J{a}'),

((state[0], 0), f'Empty J{b}'),

((state[0] - a_to_b, state[1] + a_to_b),

f'Pour J{a} into J{b}'),

((state[0] + b_to_a, state[1] - b_to_a),

f'Pour J{b} into J{a}')

]Now for the BFS. We’ll start by initializing a bunch of stuff - the initial state, the node exploration queue, the set of all visited states, a dictionary documenting what is the previous node of each visited node, and a dictionary containing the description of actions required to arrive from some node to another.

state = (0, 0)

q = [state]

visited = {state}

prev = {state: None}

action = {}As for the BFS itself, we explore nodes through the queue, looking at neighbors and adding them to the queue whenever we encounter a novel state, taking care of all the bookkeeping.

while len(q) > 0:

curr_state = q.pop(0)

if is_solved(curr_state):

break

for neighbor, action_description in get_neighbors(curr_state):

if neighbor not in visited:

prev[neighbor] = curr_state

action[neighbor] = action_description

visited.add(neighbor)

q.append(neighbor)And finally, we need to see if we arrived at a solution. If we did, we can reconstruct the process by going backwards

using the prev and action dictionaries from the final curr_state until we get to the initial state.

if not is_solved(curr_state):

print('No solution...')

else:

instructions = []

while prev[curr_state] is not None:

instructions.insert(0, action[curr_state])

curr_state = prev[curr_state]

print('\n'.join(instructions))Here are some sample runs:

Enter jug A volume: 3

Enter jug B volume: 5

Enter target volume: 4

Fill J5

Pour J5 into J3

Empty J3

Pour J5 into J3

Fill J5

Pour J5 into J3

-----------------------

Enter jug A volume: 7

Enter jug B volume: 5

Enter target volume: 6

Fill J7

Pour J7 into J5

Empty J5

Pour J7 into J5

Fill J7

Pour J7 into J5

Empty J5

Pour J7 into J5

Fill J7

Pour J7 into J5

-----------------------

Enter jug A volume: 6

Enter jug B volume: 4

Enter target volume: 1

No solution...

-----------------------

Enter jug A volume: 11

Enter jug B volume: 5

Enter target volume: 8

Fill J11

Pour J11 into J5

Empty J5

Pour J11 into J5

Empty J5

Pour J11 into J5

Fill J11

Pour J11 into J5

Empty J5

Pour J11 into J5

Empty J5

Pour J11 into J5

Fill J11

Pour J11 into J5

Beyond water jugs

While more mathematical interpretations of the water pouring puzzle exist, the general approach can be applied to other puzzles where you need to take a series of actions, for example the 15 puzzle, Rush Hour-style puzzles or puzzles in the river-crossing style I mentioned at the beginning.

Let’s try the approach with the following puzzle:

You and three other friends found yourselves in a dark cave with a torch that will last 12 minutes. There’s enough room for only two to walk outside together, but one of them will need to go back with the torch. You only need 1 minute to leave the cave, but your friends need a little more time: 2, 4 and 5 minutes. When two people walk together the faster one waits for the slower one. How can you all exit the cave safely?

from itertools import combinations

# State is represented as a 4-tuple:

# index 0 is a tuple of all people still inside the cave

# index 1 is a tuple of all people outside

# index 2 is True if the torch is inside the cave

# index 3 is the time left till the torch runs out

state = ((1, 2, 4, 5), tuple(), True, 12)

def sorted_tuple(x):

return tuple(sorted(tuple(x)))

def get_neighbors(state):

neighbors = []

if state[2]: # Torch is inside - get states of

# all possible pairs who can go outside

for pair in combinations(state[0], 2):

neighbors.append((sorted_tuple(set(state[0]) - set(pair)),

sorted_tuple(state[1] + pair),

False, state[3] - max(pair)))

else: # Torch is outside - get states of

# all people who can take it back inside

for person in state[1]:

neighbors.append((sorted_tuple(state[0] + (person, )),

sorted_tuple(set(state[1]) - {person}),

True, state[3] - person))

return neighbors

def is_solved(state):

# All people are outside and the torch hasn't run out

return len(state[1]) == 4 and state[3] >= 0

def describe_action(prev_state, new_state):

if new_state[2]: # The torch was brought inside

return f'{list(set(new_state[0]) - set(prev_state[0]))[0]}'

f'goes back with the torch'

else: # The torch was taken outside

pair = " and ".join(map(str, list(set(new_state[1]) -

set(prev_state[1]))))

return f'{pair} go outside together'

q = [state]

visited = {state}

prev = {state: None}

while len(q) > 0:

curr_state = q.pop(0)

if is_solved(curr_state):

break

for neighbor in get_neighbors(curr_state):

if neighbor[3] < 0:

continue # The torch has already run out,

# no solution will come out of this state

if neighbor not in visited:

visited.add(neighbor)

q.append(neighbor)

prev[neighbor] = curr_state

if not is_solved(curr_state):

print('No solution exists...')

else:

instructions = []

while prev[curr_state] is not None:

instructions.insert(0, describe_action(prev[curr_state], curr_state))

curr_state = prev[curr_state]

print('\n'.join(instructions))And the result:

1 and 2 go outside together

1 goes back with the torch

4 and 5 go outside together

2 goes back with the torch

1 and 2 go outside together

Other approaches

A few years later, in an introduction to AI class, I was introduced to several other approaches for solving problems of similar nature; most notably, the Graphplan algorithm, which can represent and incorporate more sophisticated task-specific knowledge, allowing for potentially much faster searches. The algorithm also represents problems as graphs and solutions as paths, but the structure is more complicated.