Generating an organic grid

Making Townscaper-style organic grids

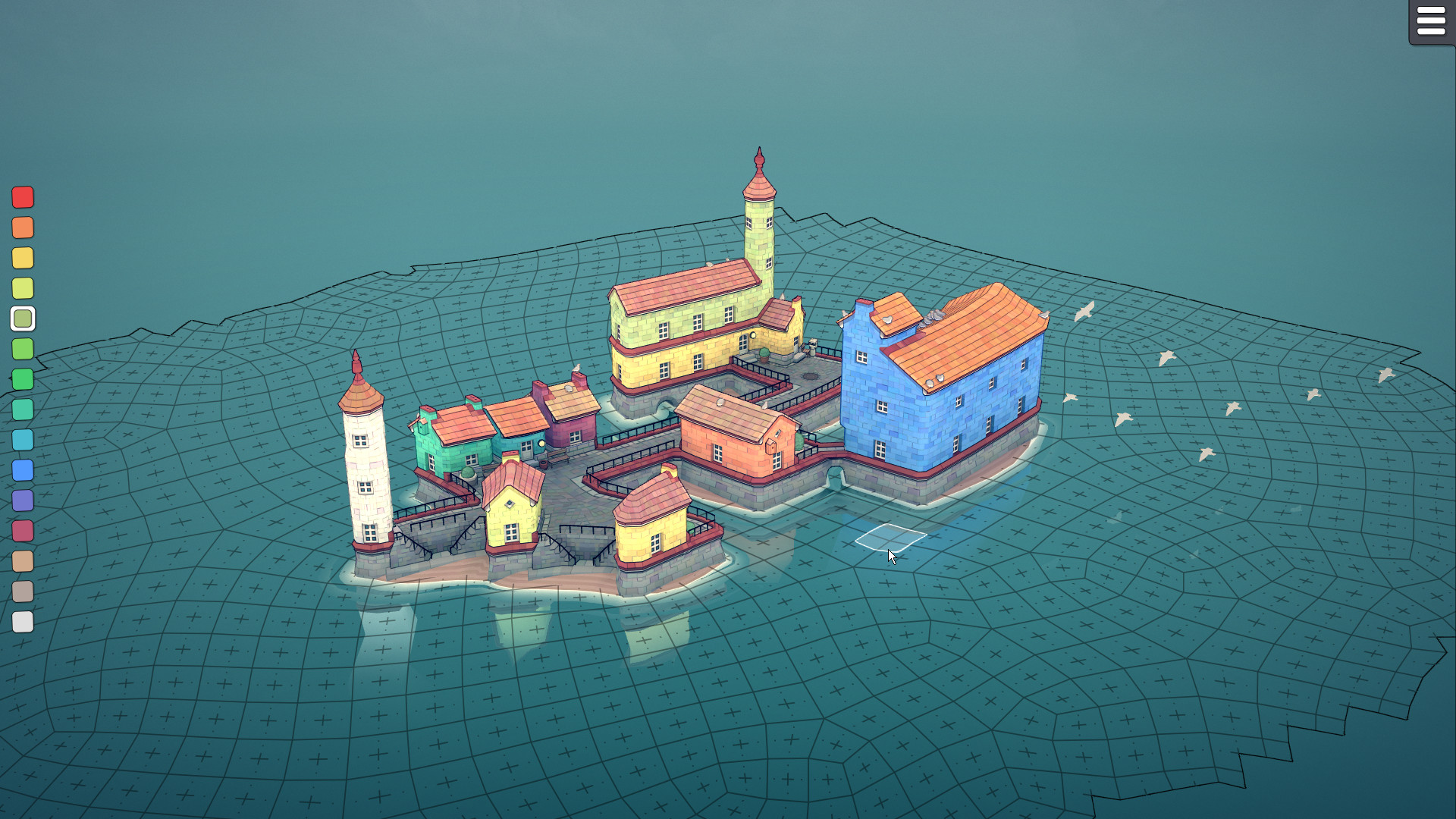

Oskar Stålberg’s Townscaper is a beautiful city-building game based on procedural generation.

One of the features I really liked is the “organic grid”:

Oskar has a great talk where he explains how various aspects of the game work, including the grid generation. I found his approach very clever but also very different from what I’d intuitively try, so I was curious to try my own approach at generating such a grid. This involved a lot of trial and error (mostly error), but I’m pretty satisfied with the end result.

Part 1: Generating a quadrilateral mesh

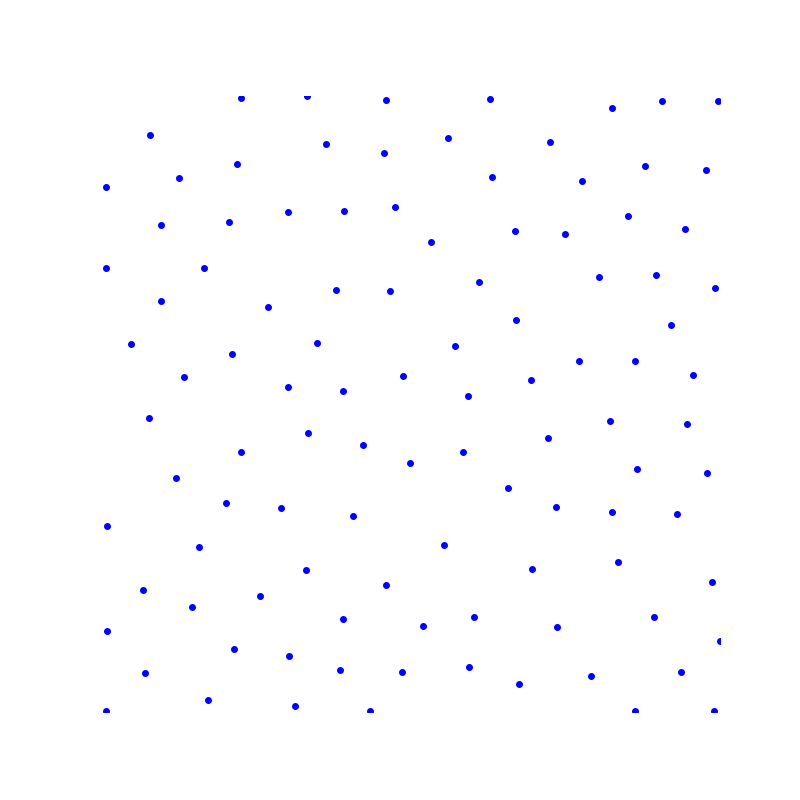

The first step is to sample 2D points using Poisson disk sampling:

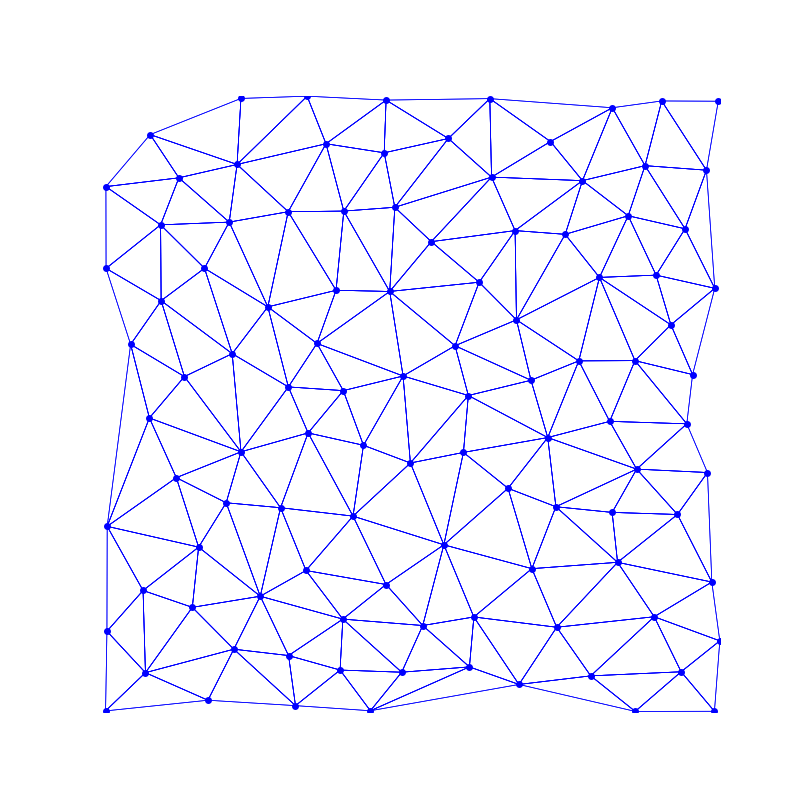

This is followed by a Delaunay triangulation and filtering out triangles with too-obtuse angles (I chose \(0.825 \pi\) as the upper threshold):

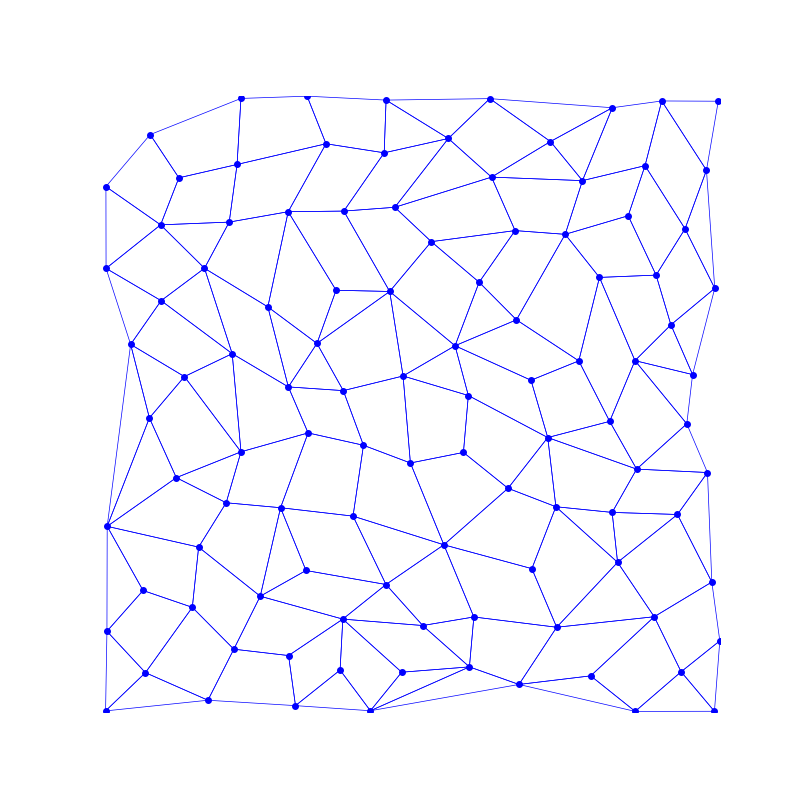

Then, triangles are iteratively merged to form quadrilaterals. Before merging I make sure that the resulting quadrilateral is convex and doesn’t contain angles that are too sharp (\(< 0.2 \pi\)) or too obtuse (\(> 0.9 \pi\)).

Some triangles remain as this merging technique is not guaranteed (and usually doesn’t) result in a proper quadrangulation.

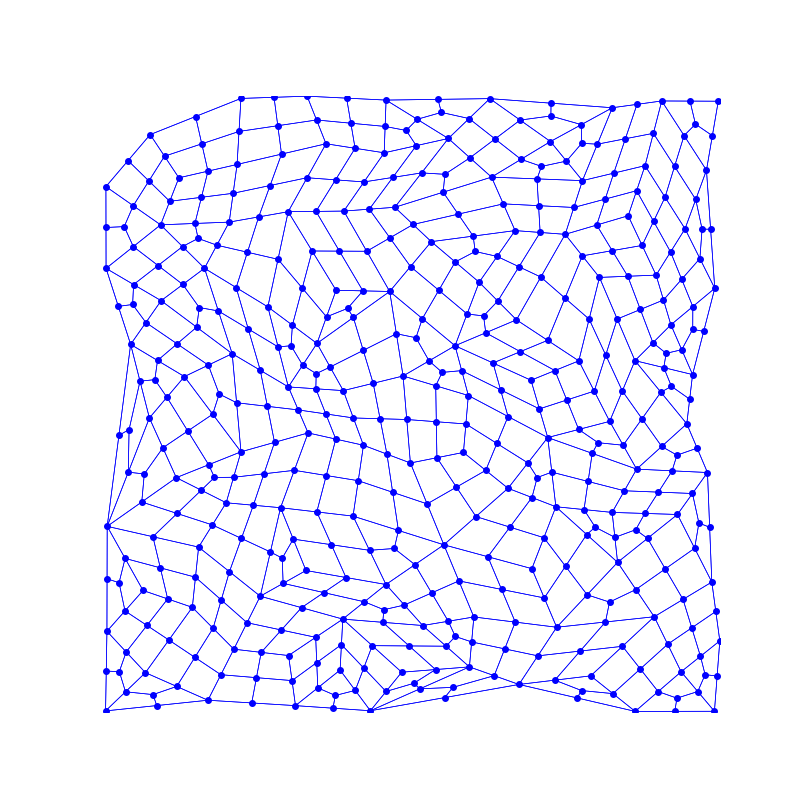

Finally, each triangle / quadrilateral is tiled with smaller quadrilaterals, to give us the final quadrilateral mesh:

Part 2: Squaring quadrilaterals

We now have a quadrilateral mesh with interesting connectivity, but it doesn’t look anything like a grid. The next part will attempt to make all quadrilaterals more square-like. For this step I tried a lot of different things which didn’t work out, such as trying to simulate particles with attraction and repulsion forces. Eventually I tackled the problem very explicitly: for each quadrilateral, I want to find a square which -

- Shares the same center of mass as the quadrilateral

- Has a predefined side length

- Is oriented such that the sum of squared distances from each quadrilateral vertex to the corresponding square vertex is minimized

Coupled with calculus, this formulation admits a closed-form solution for the square angle which looks quite good:

Using this technique we can iterate over the quadrilaterals, and accumulate for each vertex the “squaring forces” from all the quadrilaterals it belongs to. This smoothly moves the vertices to create a nice grid-like structure:

Interactive demo

This part works best on desktop.

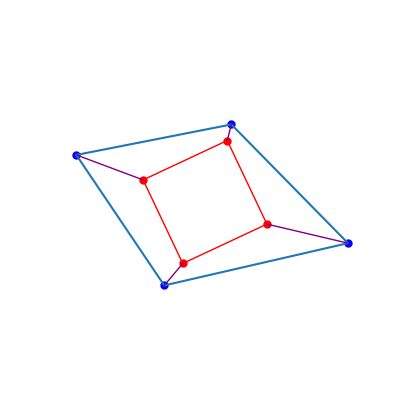

An appendix for the curious: explanation of my method for finding the “closest” square to a given quadrilateral.

We start with an arbitrary quadrilateral, and order the vertices clockwise around the center of mass. Then, given the center of mass for the square (which is the same as the quadrilateral’s) and the desired side length, we want to find an angle \(\alpha\) which minimizes the sum of squared distances between quadrilateral vertices and square vertices. The squared distances were chosen because

- The resulting optimization problem is easier

- It supports the intuition that we want to move vertices as little as possible (and would rather move two vertices distance \(d\) than one vertex distance \(2d\))

Since the quadrilateral vertices are in clockwise order, if we specify the square vertices in clockwise order as well then we could choose an arbitrary correspondence (with matching order) and find an angle that minimizes the sum of square distances.

Here are the square vertices for some \(\alpha\) in clockwise order (assuming we set the center of mass to \((0, 0)\)):

\[(r \cdot \cos \alpha, r \cdot \sin \alpha)\] \[(r \cdot \sin \alpha, -r \cdot \cos \alpha)\] \[(-r \cdot \cos \alpha, -r \cdot \sin \alpha)\] \[(-r \cdot \sin \alpha, r \cdot \cos \alpha)\]And here is the total distance we want to minimize, as a function of \(\alpha\):

\[D(\alpha) = \sum_{i=1}^{4}{(x_i - x_i')^2 + (y_i - y_i')^2}\]Where \((x_i, y_i)\) are the coordinates of quadrilateral vertex \(i\), and \((x_i', y_i')\) the coordinates of square vertex \(i\).

After substituting the square vertex coordinates, expanding and reorganizing we finally get:

\[D(\alpha) = \sum_{i=1}^{4}{(x_i^2 + y_i^2)} + 2r\cos\alpha(-x_1 + y_2 + x_3 - y_4) + 2r\sin\alpha(-y_1 - x_2 + y_3 + x_4) + 4r^2(\sin^2\alpha + \cos^2\alpha)\]To find an \(\alpha\) that minimizes \(D(\alpha)\) we want to find the derivative of \(D(\alpha)\) with respect to \(\alpha\), \(D'(\alpha)\). The first and last elements are constant (with respect to \(\alpha\)), so we get :

\[D'(\alpha) = 2r\sin\alpha(x_1 - y_2 - x_3 + y_4) + 2r\cos\alpha(-y_1 - x_2 + y_3 + x_4)\]Equating the derivative to zero and solving we finally get:

\[\alpha = \arctan(\frac{y_1 + x_2 - y_3 - x_4}{x_1 - y_2 - x_3 + y_4}) + k\cdot\pi, k = 0, 1\]We’re almost there: one value of \(k\) will give us an \(\alpha\) that minimizes \(D(\alpha)\), and the other maximizes \(D(\alpha)\). This makes sense - take the best square orientation and, keeping the same vertex correspondence, rotate it by 180 degrees, and you’ll get the worst orientation. To choose \(k\) we can compute the second derivative and choose a \(k\) for which the second derivative is positive.

\[D''(\alpha) = 2r\cos\alpha(x_1 - y_2 - x_3 + y_4) + 2r\sin\alpha(y_1 + x_2 - y_3 - x_4)\]