The faulty digital clock problem

Telling the time with a faulty digital clock and constraint propagation

You enter the escape room alone, knowing it’s not a good idea. As the door locks, you notice only two things in the room: a note and a digital clock.

To solve the crime

Go back in time

It happened at Midnight

Or so says the wee mite

Why do all escape rooms have to be so easy? But as you reach for the clock, a woeful sight strikes your eyes:

“Oh, bother”, you sigh. Some LED segments are faulty, and this is a simple clock, with only “forward” buttons to adjust the time. Now you have to orient yourself around each of the digits, preferably without looping over too many times. As you start pondering the most efficient strategy for doing that, you realize it’s too late: you’ve been nerd-sniped. The escape room doesn’t matter, this specific instance of the problem doesn’t matter - you’re going to write a general program to solve it! Fortunately you always carry a pencil, which you promptly apply to the note paper to hack at the problem.

The problem

Given a faulty display for a single digit (that is, a display where some of the LED segments are always off regardless of which digit is displayed), and the ability to increment the digit (looping around 9 to 0), we want to “orient around the display”, i.e. iterate through the digits until we unambiguously know which digit is currently displayed. For sufficiently faulty displays, there might not be a single digit where the LEDs uniquely identify a single digit. However, since the digits are iterated in a fixed sequence, the problem is sufficiently constrained to be always solvable, even with only one functional LED (though this is not immediately obvious). In this post we’ll approach the problem as a constraint satisfaction problem, specifically using a simple version of constraint propagation.

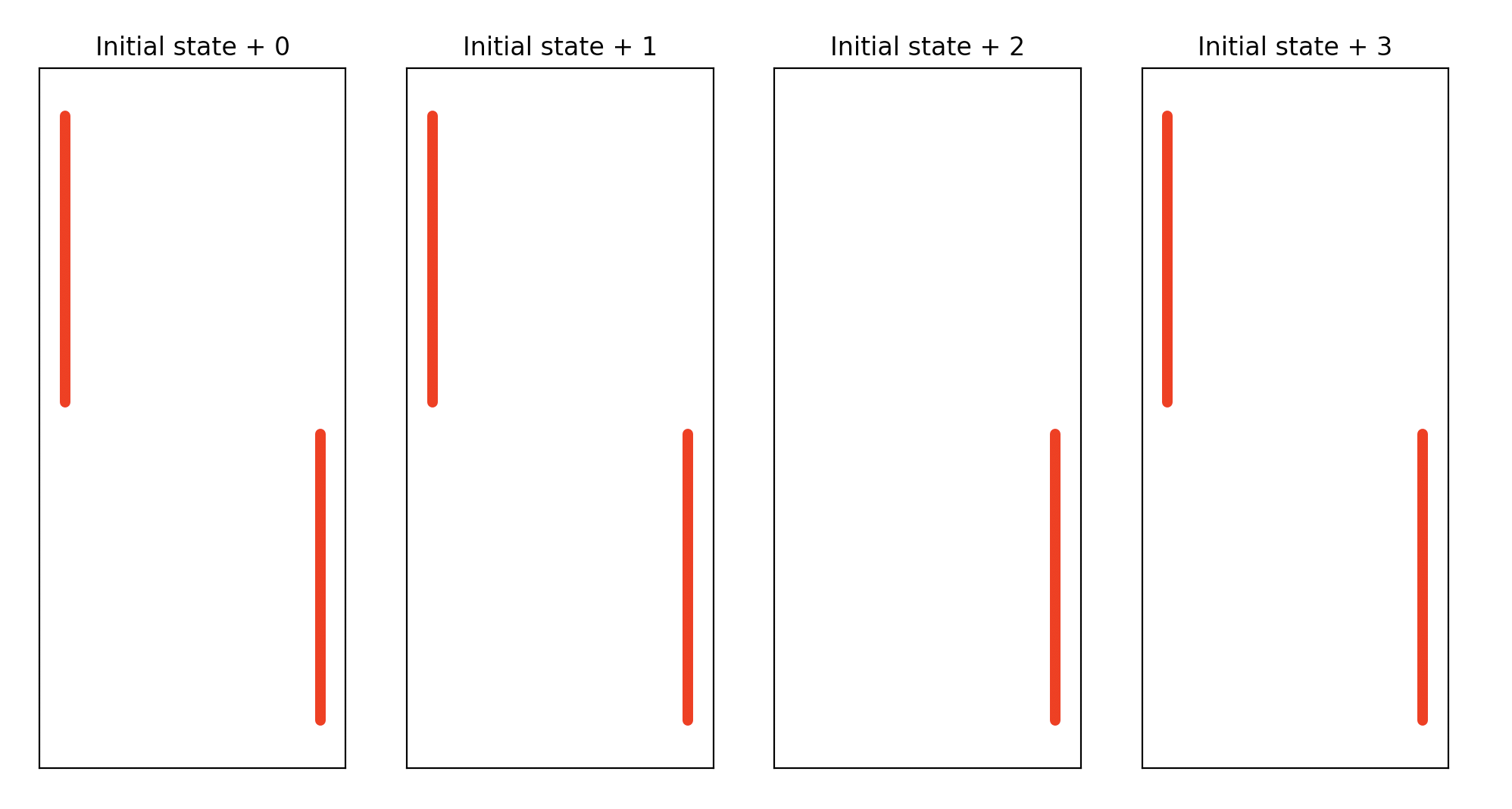

Let’s observe the following sequence of digits on some faulty display:

And let’s uncover the original digits.

The solution

Without even looking at the display, we know it must be showing one of the digits 0-9. This is our domain. Looking at the initial state, we can further constrain the possible values of the digit - for example, it can’t be 1 as the top-left segment is on. We can thus constrain all the states, but this isn’t enough to get to a solution. However, there are also pairwise constraints between the states, since consecutive states represent consecutive digits. As the second state (“Initial state + 1”) can’t represent 1 (similarly to the first state), the first state can’t be 0, even though the LED patterns in the first state are compatible with 0. Therefore our strategy is going to include finding the initial constraints, and then propagating them along the sequence. Note that they work both ways - just by looking at the initial state we can know that the next state isn’t going to be 2.

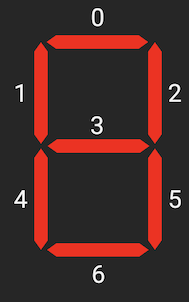

We’ll start by assigning an index to each segment:

And proceed by defining for each digit which segments should be on:

digits_segments = [

[1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1], # 0

[0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0], # 1

[1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1], # 2

[1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1], # 3

[0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0], # 4

[1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1], # 5

[1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1], # 6

[1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0], # 7

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1], # 8

[1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0] # 9

]We can also represent the faulty displays of the four consecutive states depicted above:

faulty_displays = [

[0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0]

]Now we’ll generate the candidates for each state just by using the unary constraints, i.e. for each state ruling out digits which should have a segment off that is turned on in that state.

def get_candidates(display_mask):

return {

digit for digit, digit_segments in enumerate(digits_segments)

if all([digit_segment >= display_segment

for digit_segment, display_segment

in zip(digit_segments, display_mask)])

}

candidates = [get_candidates(display) for display in faulty_displays]

print(candidates)[{0, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9},

{0, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9},

{0, 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9},

{0, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9}]

Seems right, but also far from a solution.

We’ll now apply the pairwise constraints, in two passes - one forward and one backward. In each pass, we further constrain each state according to the feasible candidates of the previous / next state. For fun, we’ll print the candidates after the forward pass, before the backward pass.

for i in range(1, len(candidates)):

candidates[i] = candidates[i].intersection({(d + 1) % 10

for d in candidates[i - 1]})

print(candidates)

for i in range(len(candidates) - 2, -1, -1):

candidates[i] = candidates[i].intersection({(d - 1) % 10

for d in candidates[i + 1]})

print(candidates)[{0, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9}, {0, 9, 5, 6}, {0, 1, 6, 7}, {8}]

[{5}, {6}, {7}, {8}]

And there we have our solution.

Some notes

- There’s a small modification we can do to make the unary constraints stronger: we can keep track of which LED segments are functioning, and use that information to rule out digits which should have one of those segments on (but is off in the display). This for example will rule out

0,4,5,6,8,9from the third state in our example. - I think the formal equivalent of what most people would do is to apply the unary constraints, then start a backtracking search, i.e. guess at some digit based on the unary constraints and see if it fits, and going back once they see a mistake. Backtracking is widely used in constraint satisfaction problems, although in this case constraint propagation was sufficient. Usually, constraint propagation is applied before backtracking to make the search space smaller.

- This is an extremely simple constraint propagation problem - it’s highly constrained, all the constraints are either unary or binary, and the binary constraints form a linear graph. This is why constraint propagation alone is sufficient to find all feasible solutions, and why a simple forward and backward pass are enough.

- The general problem of constraint satisfaction is NP-complete.

- Real-world use cases of constraint satisfaction problems include static language type inference, circuit verification, various problems in operations research, and more. There are even layout engines based on constraint solvers.

The End

The door unlocks behind you. “Huh! Beat you to it!” exclaims your friend. “Wait, you haven’t even – oh, not again!”