Heads or Tails

Conceptual introduction to classical machine learning in JS

A few months ago I gave an “introduction to classical ML” workshop to a team of full-stack developers. The idea was to give a conceptual introduction, break down the very abstract “let’s design an algorithm that improves with more data”, and demonstrate how you’d approach this in practice.

The workshop was accompanied by an exercise in JS, “Heads or Tails”, which is what this post is going to be about.

Heads or Tails

In this exercise you’ll implement the brains behind the blockbuster video-game, “Heads or Tails”, which tests the player’s ability to randomly choose between heads and tails. The game guesses the player’s next choice, and should these choices exhibit any patterns, the game will use these patterns to gain an advantage over the player.

During the exercise, you’ll implement increasingly sophisticated algorithms for predicting the player’s next choice given their choice history, with the game visualizing the algorithms’ predictive power on your choices as a player. Ready to be unpredictable?

00 Preparations

- Download this html file

- Open it in your favorite web IDE and navigate to

YOUR CODE GOES HERE - Open it in a browser too (with js enabled)

01 Hello, world

As previously mentioned, you’ll play two roles: of the developer implementing the learning algorithms, and of the player being tested for predictability.

In the provided html file, one “prediction algorithm” has been implemented, which just uses

Math.random to predict the player’s choice. It is therefore very poor as a prediction algorithm,

but it’ll assist you in understanding what’s going on and provide a baseline for comparison.

In the browser, start pressing “1” (for heads) and “2” for (tails) randomly, and you’ll see a line chart being extended as you play. The chart depicts the prediction algorithm’s score: it gains a point every time it predicts correctly, and loses a point every time it’s wrong.

In the code, look for the function predictRandom - this is the random prediction implementation.

Any function you’ll write whose name starts with “predict” will be integrated to the game and you’d be able to see its predictive performance.

The functions you’ll implement take one parameter - history, which is an array with the player’s choice history (in the current game).

Choices are represented as strings - “H” for heads, “T” for tails. The function needs to return the prediction for the player’s next choice (again, “H” or “T”).

Add two simple prediction functions:

- One that always predicts the player will choose heads

- And another that always predicts the player will choose tails

Refresh the page and, using the score visualization, make sure the functions behave as you would expect.

02 Reflection

Before we move on to more sophisticated algorithms, let’s take a step back and look at what we’re trying to achieve.

Using the functions we added in section 01, it’s easy to see that when the player always makes the same choice (say, tails),

the respective prediction function is significantly better than the predictRandom strategy.

But, unless you have a strong preference to either choice, if you try to behave randomly these const-predicting functions

won’t perform much better than random.

We’d like to formulate stronger prediction strategies, such that even when we try to confuse the predictor, it’ll pick up on our patterns (assuming they exist) and will be notably better-performing than the random strategy. That is, unless we’ll manage to be truly random, which (spoiler alert) most humans aren’t capable of.

So: if you write an algorithm that achieves a similar score to the random predictor, that algorithm can’t find your patterns. If it gets significantly better score, that means a) that you’re relatively predictable, and b) that the algorithm managed to pick up on your patterns.

Another point for thought: what does it take for an algorithm to achieve significantly worse scores than the random predictor?

03 Warming up

Let’s assume the player has a strong preference for one of the choices. We can write a function that finds this preference and uses it to predict the next choice. Implement such a function.

For example: if this is the player’s choice history:

HTTHTTHTTHTTHHHTHT

We can see that the player picked heads 8 times, and tails 10 times. Therefore we’ll predict “tails”.

As the game progresses, the majority choice might change, and your function’s prediction will reflect that.

04 Getting serious

The previous function was very simplistic. Let’s write a more sophisticated version of it: suppose there’s some consistency in the player’s behavior. Say, the player makes long runs of heads, long runs of tails, and occasionally switches between them. Or, that they try to be “unpredictable” but instead end up just alternating between them, choosing “heads-tails-heads-tails”.

In such cases, even though there might not be a generally preferred choice, we might be able to exploit finer patterns.

Let’s look again at the choice history from the previous section: HTTHTTHTTHTTHHHTHT.

Instead of taking the majority of choices, we note that the player’s last choice is “tails”, and so we’ll look only at choices

made after tails. Here they are, highlighted:

HTTHTTHTTHTTHHHTHT.

After choosing tails, the player chose tails again 4 times, and heads 5 times. Therefore, in this case, we’ll predict “heads”.

Implement a prediction function that uses the algorithm described here to make predictions.

05 When the going gets tough

Alright, now we’re in the grown-ups’ league. In this section I’ll guide you through implmeneting a (simple version of a) real machine-learning algorithm: decision trees.

The implementation requires a bit more work so you can treat it as a small project.

Ready? Here we go.

In the previous section we looked at the player’s last choice, hoping to exploit patterns related to it. Playing around yourself, you probably noticed there can be longer-than-2 runs, and we’d like to exploit those too. We could, in theory, extend the technique used in the previous section: enumerate all the possibilities for, e.g. a 6-choice-long run, and take the majority for each case. But that’s an extremely specific prediction strategy - to get meaningful data for longer runs we’d need to play a lot of time, and we might be missing more obvious patterns. What can we do?

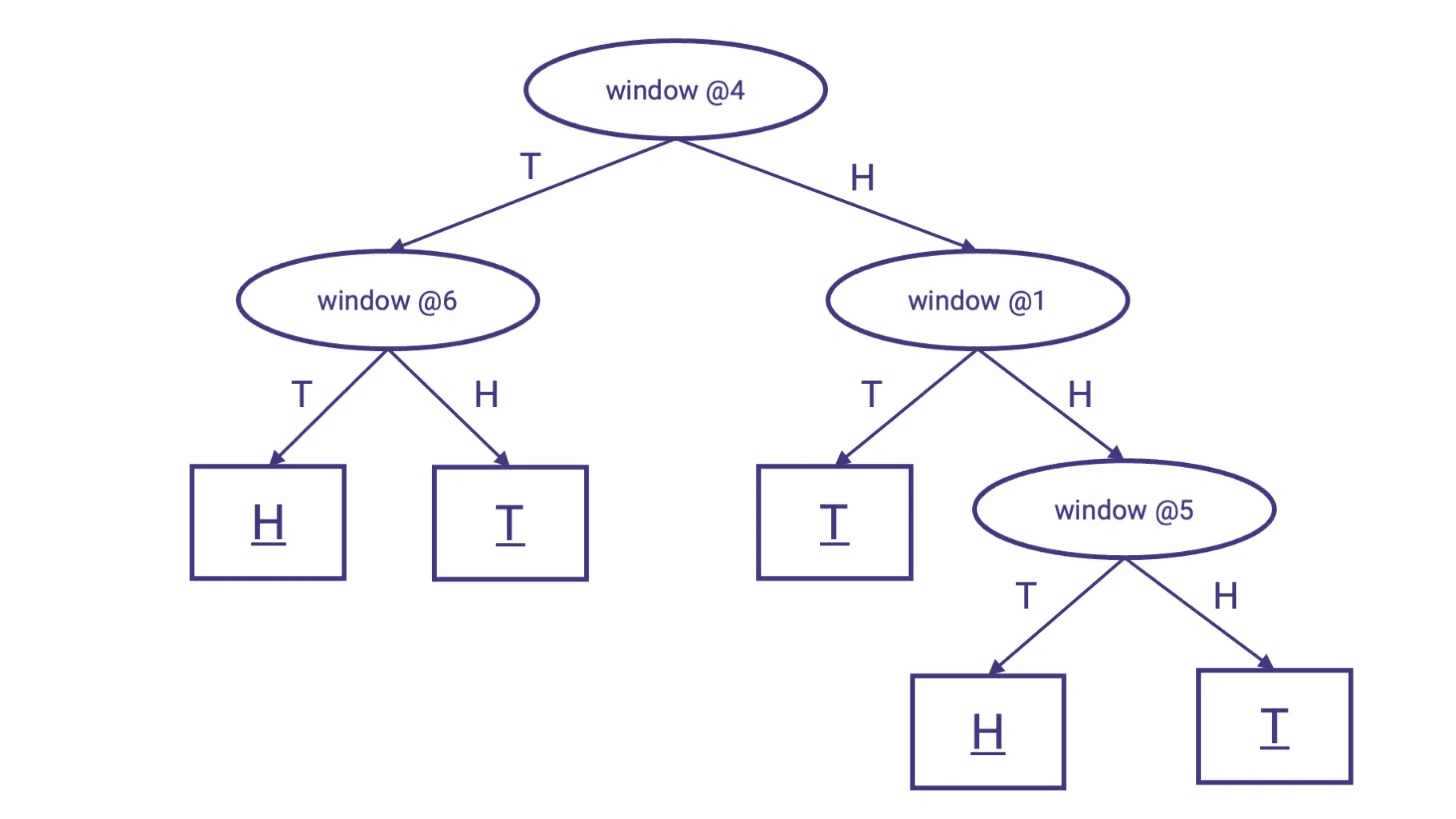

A decision tree is a classical machine-learning algorithm, where each prediction is decided through a sequence of questions, where the questions are leading us down through nodes until we make a prediction.

In our case, if we look at a history window of length 6, a decision tree might look like this:

What do I mean by “history window” of size 6? Suppose this is the player’s choice history: HTTHTTHTTHTTHHHTHT.

Then this is the last window of size 6: HTTHTTHTTHTTHHHTHT.

Using the player’s choice history, we can construct a training set of all the length-6 windows and the choice that came right after them, which we’ll use to look for patterns:

| Window | Choice after window |

|---|---|

| HTTHTT | H |

| TTHTTH | T |

| THTTHT | T |

| HTTHTT | H |

| TTHTTH | T |

| … | … |

| THHHTH | T |

In the first row (HTTHTT), “window @1” is the first choice in the window - H. “window @3” is T, “window @6” is T as well, and so on.

Back to decision trees. I’ll divide the implementation to two parts - representing a decision tree, and constructing the decision tree given data.

Part 1: Decision tree representation

This part is pretty programmatic - decide how you want to represent a decision tree, without worrying about how you’d actually construct the decision tree, and implement this representation.

You could go all-in OOP and create a TreeNode class with pointers to 2 child nodes (which might be predictions or additional decision nodes); you could use simple data structures (arrays, objects) with appropriate functions; you could use functional programming; or whatever else you fancy.

Make sure you can easily construct a decision tree, and that you can use one to make predictions.

Part 2: Constructing a decision tree

Now we’re ready to tackle the next part: constructing a decision tree based on a player’s choice history. What we’re actually aiming to do, is find a bunch of tests on the history window, which maximally separate windows which were followd by “heads” from windows that were followed by “tails”.

Part 2.1: Creating a training set

As preparation for constructing the decision tree, we want to extract a training set (similar to the table shown above) from the choice history. Implement a function that takes the choice history and returns a sequence of training pairs: choice window, and choice following window.

Part 2.2: Measuring homogeneity

Given a set of choices, we want to be able to measure how homogenous - “pure” - they are. If all the choices are the same, that’s maximal homogeneity. If they distribution 50-50 - that’s minimal homogeneity.

We will use this metric to evaluate potential decision tree structures, and pick tests that make a set of poorly-separated choices to two purer sets.

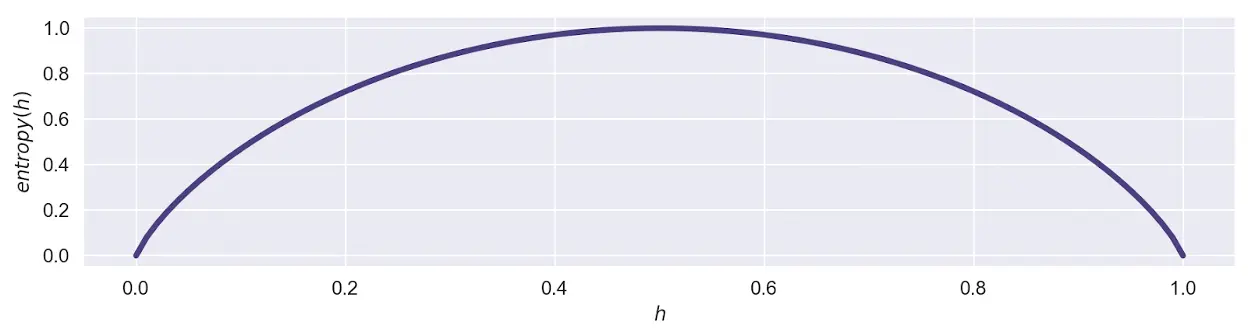

The measure we’ll define is called entropy (the one from information theory, not thermodynamics). It actually measures the opposite of homogeneity - heterogeneity, and goes like this:

Suppose in a given set of choices, \(h\) denotes the proportion of “heads” choices, and \(t\) the proportion of “tails” choices (\(h + t = 1\)). Then:

\[entropy(h, t) = -(h \cdot \log_2 h + t \cdot \log_2 t)\]Since \(h + 1 = 1\), we can also write:

\[entropy(h, t) = -(h \cdot \log_2 h + (1 - h) \cdot \log_2 (1 - h))\]The following chart visualizes the entropy for each \(h\) between 0 and 1:

Implement a function that computes the entropy of a given set of “heads” / “tails” choices. Make sure it agrees with the chart above.

Part 2.3: Actually constructing the decision tree

OK, we’ve been through a lot up until now, but bear with me - this is the final push.

I’ll first describe the algorithm and then explain it.

We’ll use a pair of variables, X and y, to denote our training set: X contains a sequence of windows, and y contains a sequence of choices following the windows. X and y are corresponding, so for example the 11th element of y is a choice that came after the 11th element of X.

ConstructDecisionTree(X, y)

- If X contains 5 windows or less:

- Return a prediction node that predicts the majority in y

- For each possible test index “idx” (choice 1 / 2 / 3 in the window etc.):

- \(X_h, y_h\) <- all windows / choices in X / y where window[idx] == “h”

- \(X_t, y_t\) <- all windows / choices in X / y where window[idx] == “t”

- Compute the weighted average entropy after splitting by idx:

- Compute how much the entropy decreased: \(improvement = entropy(y) - newEntropy\)

- Store all the variables (\(X_h, X_t, y_h, y_t, improvement, idx\)) somewhere

- Find the best split (highest \(improvement\))

- If the best \(improvement\) is less than 0.1:

- Return a prediction node that predicts the majority in y

- Otherwise, retreive \(X_h, X_t, y_h, y_t, idx\) corresponding to the best \(improvement\)

- \[rightBranch \leftarrow ConstructDecisionTree (X_h, y_h)\]

- \[leftBranch \leftarrow ConstructDecisionTree (X_t, y_t)\]

- Return a decision node that tests the window at \(idx\): if it’s “heads”, pass computation to \(rightBranch\); if it’s “tails”, pass computation to \(leftBranch\)

The algorithm might not be trivial, but it’s very elegant, and we’ll now break it down.

First off, you probably noticed that the algorithm is recursive. At every step, the algorithm tries to find the optimal test for spliting the training set.

The recursion’s stopping criteria is one of two:

- We don’t have enough windows + choices pairs to create another tree (I chose 5 arbitrarily - you can play with that choice)

- We haven’t found a test whose split improves purity enough to justify adding another level to the tree (again, I chose 0.1 arbitrarily)

In any case, if we stopped - we’ll return a prediction node that predicts the majority of the history at the current node.

If we haven’t stopped, that means we have a test we’d like to split by. In thise case we’ll divide \(X\) and \(y\) according to the test, and construct two more corresponding decision trees with a recursive call. Then we compose those trees along with a test to see which subtree needs to handle the current case.

How do we measure the quality of each candidate test? Remember the entropy measure we defined? The higher it is, the more “impure” our set is. So we want to find the test that decreases entropy as much as possible. After splitting, we calculate the entropy for each of the new sets, and calculate the weighted average of the entropies to compare to the initial value before splitting. The improvement is then the difference bewteen the pre-split entropy, to the weighted-average entropy after the split.

And that’s it! These are all the pieces we need to construct a decision tree. Well done!

If you’d like more intuition, this link contains a wonderfule, visual introduction to decision trees.

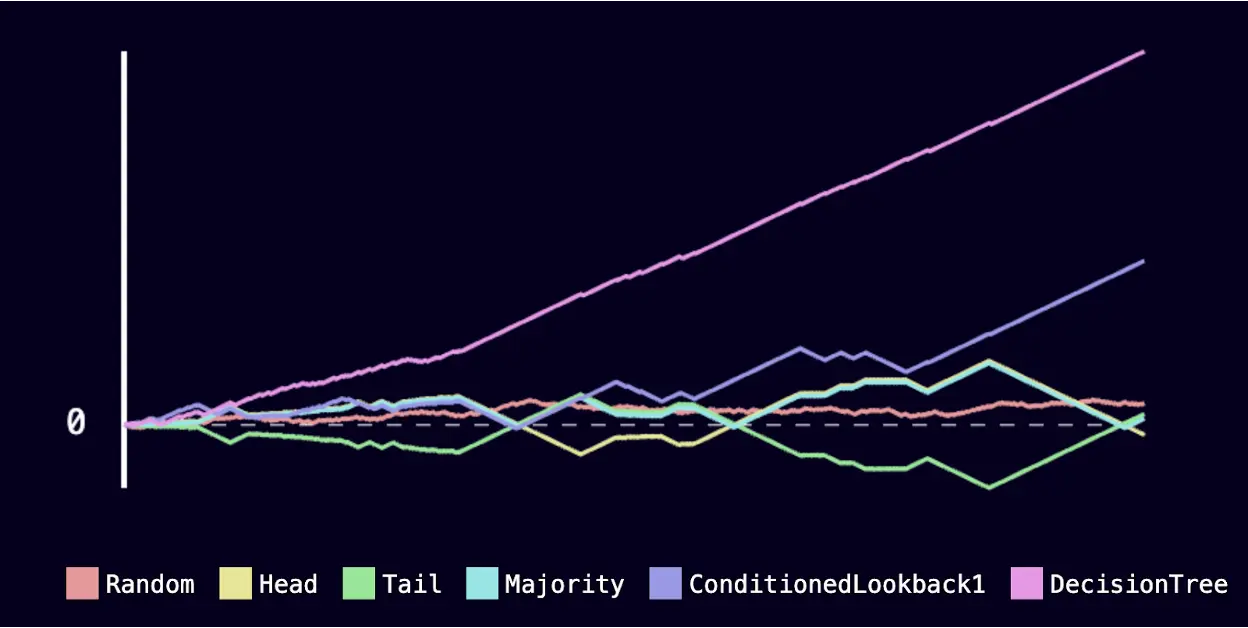

06 Some more reflection

Hopefully you’ve managed to properly implement the decision tree predictor, and witnessed that it’s pretty good at learning your patterns. That’s cool!

At least for me the decision tree is a great predictor:

A nice way to convince ourselves that the computer isn’t somehow cheating is to feed properly random choices and make sure all strategies behave like predictRandom (use the browser’s devtools):

for (var i = 0; i < 200; i++) {

document.querySelectorAll('.coin')[Math.round(Math.random())].click();

}

07 Solution

My implementation of the exercise solutions is here, SPOILER ALERT.

08 Where to next?

If you enjoyed this and would like to go further, there are several directions:

- First of all you could investigate more in-depth some aspects of the decision tree implementation:

- Choice of window size, thresholds for the stopping criteria, even how much of the player’s history to construct the tree with

- You can manually play with values and try to find the optimal one

- Or use the data to find them!

- If you do use the data, you better watch out for overfitting; read about cross-validation to mitigate that.

- You can try learning about neural networks and using one of several js frameworks to implement them here

- If you’re serious about learning ML, there are a lot of platforms for that: Kaggle learn, DataCamp, Fast.ai course and many more

Good luck!