The case for better-than-random splits

Exploring issues with random splits and possible solutions

tl;dr: Random splits are common, but maybe not balanced enough for some use cases. I made a python library for balanced splitting.

Random numbers are cool, and also useful for a lot of stuff. Among others, whenever you want to balance things in some manner, random assignment is a good first choice. A load balancer which assigns tasks randomly to servers would fare quite well. This is such a simple and powerful idea that the ideas of balance and randomness are often mixed, and we perceive the results of a random process as balanced. And they are balanced - on average. Sometimes that’s good enough, and sometimes it’s not.

When random isn’t balanced enough

This

article, about random numbers in game design, provides a great example of a situation where an innocent random process leads

to undesired behavior. Using random(0, 1) <= 0.1 to determine the outcome of a positive event

which should happen 10% of the time sounds about right - the player will need about 10 attempts, maybe a little more,

maybe a little less. The “little less” part is no problem, but if we zoom on the “little more” we see that the tail of the distribution is long -

12% of players will have to make more than 20 attempts, twice as many as we (presumably) intended. If the game is long and contains,

say, 100 such events, then 40% of players will experience at least one instance where they will need as many as 50(!) attempts. Definitely not what

we want. So randomness has to be controlled.

Splitting students to study groups

Several years ago I was responsible for an intensive, several-month training course of about 100 students. The students are divided to several groups which become their primary environment within the training - lessons are held for each group separately and the instructors are fixed per group, and get to know each student quite well. There was a general consensus that the groups should be balanced, both in demographic composition and with respect to several different aptitude tests.

There was no established process for splitting the students to groups - some of my predecessors used random assignment, others performed the split manually with an Excel sheet. The person who was in charge of the previous training complained that the groups weren’t balanced, with some containing a greater percentage of weaker students, creating excessive load on the instructors of those groups and higher dropout rate in those groups. They also said that, in hindsight, the group imbalance could already be seen in the groups’ aptitude test distributions.

Fearing that some random fluke would mess things up, I started with a random split and spent about 3 hours manually balancing the groups (the schedule was tight and I didn’t want to risk getting lost here), and (related or unrelated) things turned out fine. But it was very tedious, and frustrating enough that when I had the time I wrote a script to automate the task, performing a heuristic search for a split that minimizes the distribution differences between the groups.

Balanced split search

Here is an example of using (crude) simulated annealing to search for a split that is “balanced”:

def optimized_split(X, n_partitions=2, t_start=1,

t_decay=.99, max_iter=1000,

score_threshold=.99):

"""Perform an optimized split of a dataset using simulated annealing"""

var_types = [guess_var_type(X[:, i]) for i in range(X.shape[1])]

def _score(indices):

partitions = [X[i] for i in indices]

return score(partitions, var_types)

def _neighbor(curr_indices):

curr_indices = np.copy(curr_indices)

part1, part2 = np.random.choice(np.arange(len(curr_indices)),

size=2, replace=False)

part1_ind = np.random.choice(np.arange(curr_indices[part1].shape[0]))

part2_ind = np.random.choice(np.arange(curr_indices[part2].shape[0]))

temp = curr_indices[part1][part1_ind]

curr_indices[part1][part1_ind] = curr_indices[part2][part2_ind]

curr_indices[part2][part2_ind] = temp

return curr_indices

def _T(i):

return t_start * np.power(t_decay, i)

def _P(curr_score, new_score, t):

if new_score >= curr_score:

return 1

if t == 0:

return 0

return np.exp(-(curr_score - new_score) / t)

all_indices = np.arange(X.shape[0])

np.random.shuffle(all_indices)

indices = np.array_split(all_indices, n_partitions)

best_score = _score(indices)

for i in range(max_iter):

new_indices = _neighbor(indices)

new_indices_score = _score(new_indices)

if (new_indices_score >= best_score or

np.random.random() <= _P(best_score, new_indices_score, _T(i))):

best_score = new_indices_score

indices = new_indices

if best_score >= score_threshold:

break

return [X[i] for i in indices]

def guess_var_type(x):

"""Use heuristics to guess at a variable's statistical type"""

if type(x) == list:

x = np.array(x)

if x.dtype == 'O':

try:

x = x.astype(float)

except ValueError:

pass

if not np.issubdtype(x.dtype, np.number):

return VarType.CATEGORICAL

if np.unique(x).shape[0] / x.shape[0] <= .2:

return VarType.CATEGORICAL

return VarType.CONTINUOUS

def score(partitions, var_types):

"""Score the balance of a particular split of a dataset"""

return np.min([

score_var([_get_accessor(partition)[:, i]

for partition in partitions], var_types[i])

for i in range(len(var_types))

])

def score_var(var_partitions, var_type):

"""Score the balance of a single variable in a certain split of a dataset"""

if var_type == VarType.CATEGORICAL:

unique_values = np.unique(np.concatenate(var_partitions))

value_counts = count_values(var_partitions, unique_values)

return chi2_contingency(value_counts)[1]

pvalues = []

for i in range(len(var_partitions)):

other_partitions = [var_partitions[j]

for j in range(len(var_partitions)) if j != i]

pvalues.append(ks_2samp(var_partitions[i],

np.concatenate(other_partitions))[1])

return np.min(pvalues)

def count_values(var_partitions, unique_values):

"""Count the number of appearances of each unique value in each list"""

value2index = {v: k for k, v in dict(enumerate(unique_values)).items()}

counts = np.zeros((len(var_partitions), len(unique_values)))

for i in range(len(var_partitions)):

for value in var_partitions[i]:

counts[i, value2index[value]] += 1

return countsTo summarize:

- The search process starts with an initial random split, and generates neighbors (similar splits with a pair of indices swapped).

- Solutions are scored based on the minimum p-value of the difference between each variable’s distribution among the groups, using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for continuous variables and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables (the variable types are determined using simple heuristics).

- Each neighbor is compared to the current solution; if it’s better it is immediately accepted and set as the current best solution. Otherwise it is accepted with a probability that depends on the difference in score and the current iteration, using the temperature mechanism of simulated annealing.

- This continues for a fixed number of iterations or until we have a good enough split.

Comparing the optimized split to a random split

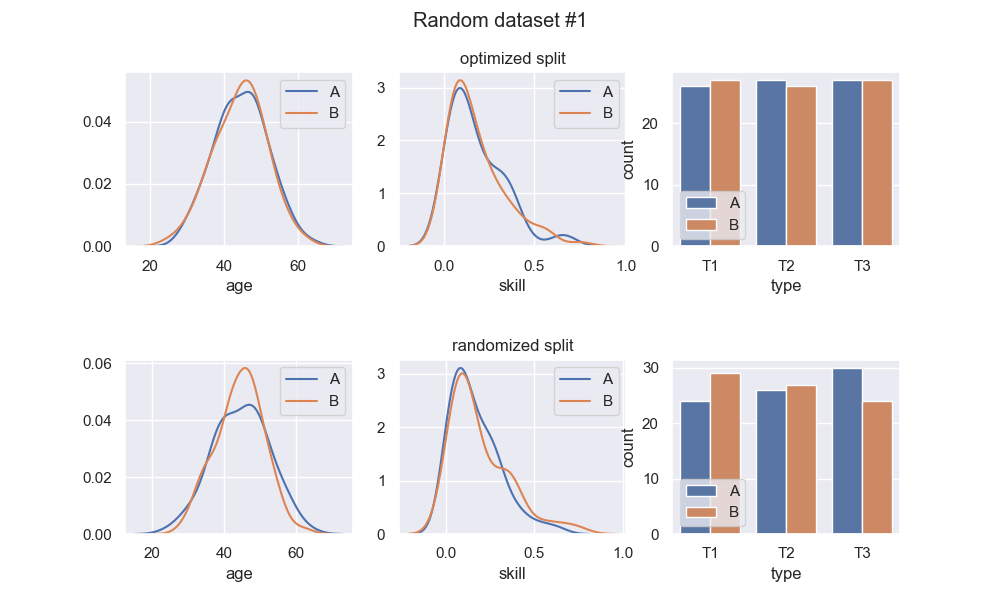

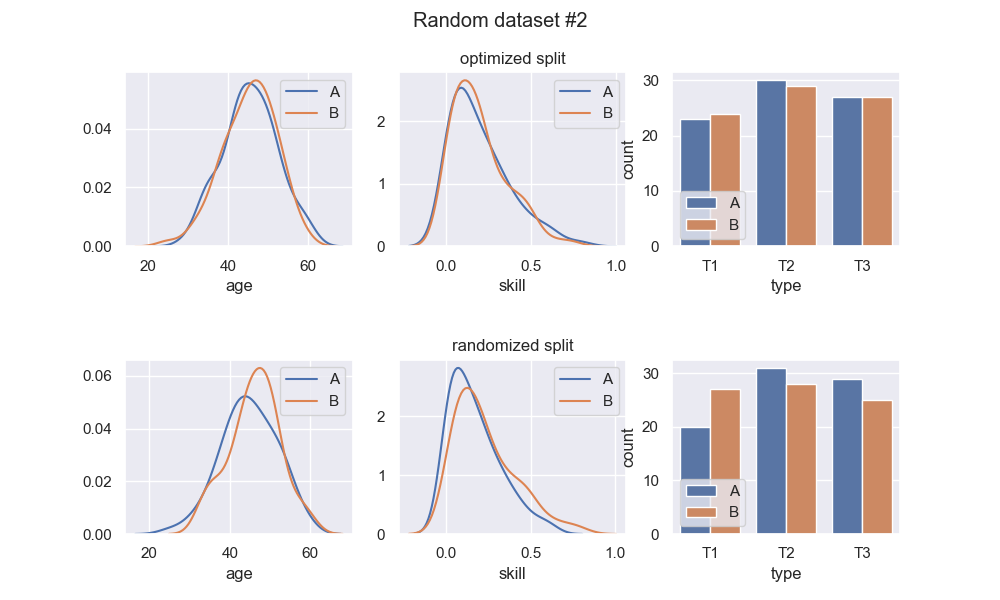

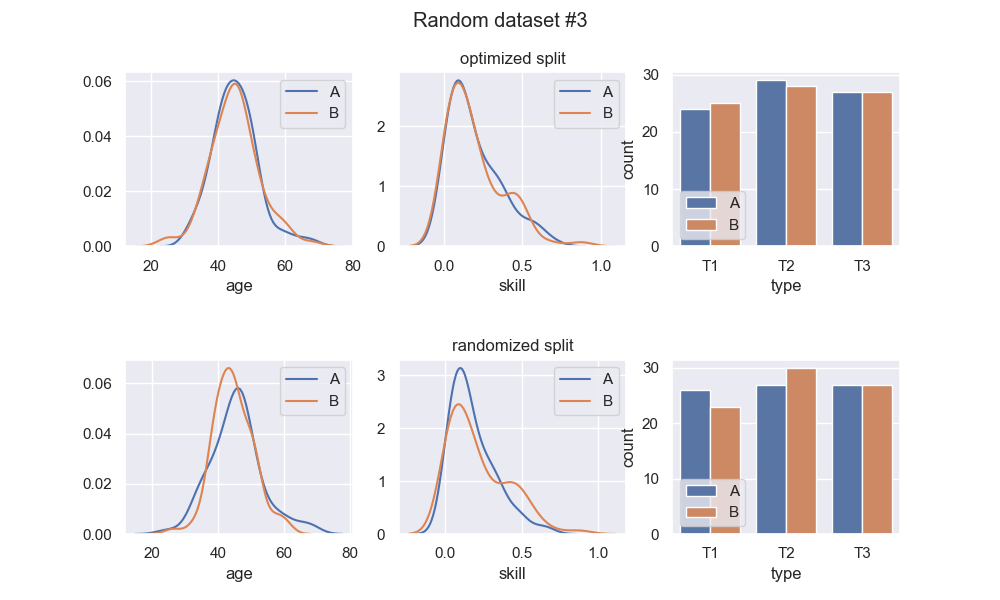

Here are 3 runs of a random dataset generation, and comparison of the optimized split with a random split:

We see that the optimized splits are indeed quite balanced, and visibly more balanced than the random splits. Regarding the random splits - they are pretty OK, in these instances. If I ran this example a thousand more times, I would definitely get instances with much greater imbalance in the random split. Whether or not this is a problem entirely depends on context. At any rate, the optimized split should be much more consistent.

Implication for experiment design

Randomized controlled trials are a type of experiment which relies on random splitting to reduce bias. For any single trial it is unlikely that a random split will create an imbalance in exactly the “right” aspect and direction to significantly change the conclusions. But it’s certainly possible, and in aggregate, over thousands of trials, it’s much more likely to happen sometimes.

Meta-experiment simulation

To get a feel for whether and how much splitting strategy could affect the conclusions of randomized trials, I ran a meta-experiment simulation where each experiment had the following set-up:

sample size ~ uniform(50, 200)

n_features ~ uniform(3, 7)

target variable (measured at end of trial) ~ normal(0, 1)

intervention effect size on target variable:

50%: 0

50%: ~ normal(1, .5)

each feature's effect size on target variable:

80%: 0

10%: ~ normal(1, .5)

10%: ~ normal(-1, .5)

generate random dataset, features ~ normal(0, 1)

split dataset to control and intervention based on splitting strategy

resolve for each subject final target variable (base + intervention + features)

accept or reject the null-hypothesis

The null hypothesis (that the treatment is ineffective) is rejected if the p-value of a t-test on the target value is less than or equal to 5%.

For each splitting strategy (random or optimized) I ran 10000 experiment simulations, counting occurrences of false positives and false negatives. A false positive is when the null hypothesis was rejected although the intervention effect was 0; a false negative is when the null hypothesis was accepted although the intervention effect was nonzero.

Results

Using a random split, 1172 experiments (out of 10k) arrived at the “wrong” conclusion - 113 false positives and 1059 false negatives. Using the optimized split, 1088 experiments arrived at the wrong conclusion, with 63 false positives and 1025 false negative. We see a significant reduction (almost 50%) in the false positive rate, which confirms that splitting strategy could affect an experiment’s results. Remember that this is a toy simulation and the numbers can depend a lot on the specific experiment set-up simulation - the key takeaway is that splitting strategy can affect the conclusions at all.

The bottom line

This could easily seem like a minor point - most of the time, random splits are perfectly good. But the ongoing replication crisis, which involves many fields in which small-n experiments are quite common, is pushing us to double-check many assumptions and currently-held best practices. Random splits are very common, and performing them in a more balanced fashion doesn’t require much effort. As the crisis probably stems from many different factors, I think it’s a good idea to start adopting various practices aimed at making experiments more robust, and balanced splits seem to be a good candidate.

balanced-splits python library

To help facilitate balanced splitting, I created a python library - balanced-splits (github) which does just that:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from balanced_splits.split import optimized_split

sample_size = 100

df = pd.DataFrame({

'age': np.random.normal(loc=45, scale=7., size=sample_size),

'skill': 1 - np.random.power(4, size=sample_size),

'type': np.random.choice(['T1', 'T2', 'T3'], size=sample_size)

})

A, B = optimized_split(df)

print('Partition 1\n===========\n')

print(A.describe())

print(A['type'].value_counts())

print('\n\n')

print('Partition 2\n===========\n')

print(B.describe())

print(B['type'].value_counts())If you have any questions regarding its use or suggestions for improvement, feel free to contact me.

Happy splitting!